Literature

AI

12 Min.

How MedTech Teams Really Extract Data Today

Adrien Sosson

Jan 15, 2026

And Why Flinn Is Prioritising Analytical Extraction First: With Intention, Not Accident

If you’ve ever worked on a CER, a PMCF report, or any kind of clinical evidence summary, you already know the unspoken truth:

Extraction is where timelines tend to stretch.

You start the day thinking, “I’ll just extract three papers before lunch.”

Suddenly it’s 6:45pm, your document has 40 highlighted sentences, 12 half-finished notes, five contradictory data points, and an Excel sheet that looks like a Jackson Pollock painting.

Because in the classic MedTech evidence workflow (search → screen → include → extract → appraise → write) extraction is the bottleneck. Slow. Messy. Unpredictable.

Most MedTech teams extract 40–60 data points per paper. Some of those “data points” aren’t numbers at all, they’re arguments. And a single paper can easily take 45–120 minutes.

For our customers, extraction consumes the most time, money, and energy in their literature review process, yet the regulators never talk about how it’s supposed to be done.

So we decided to look closely. And we want to share what we found and how it shaped how we think about extraction at Flinn.

The first twist we didn’t see coming: There isn’t one extraction system. There are two.

And they couldn’t be more different.

Most teams don’t even realize they’re choosing one.

But whichever system they follow becomes the blueprint for their entire evidence strategy, and once you introduce AI into that system, the logic spreads automatically.

So let’s open the curtain and talk about how MedTech teams really extract data today.

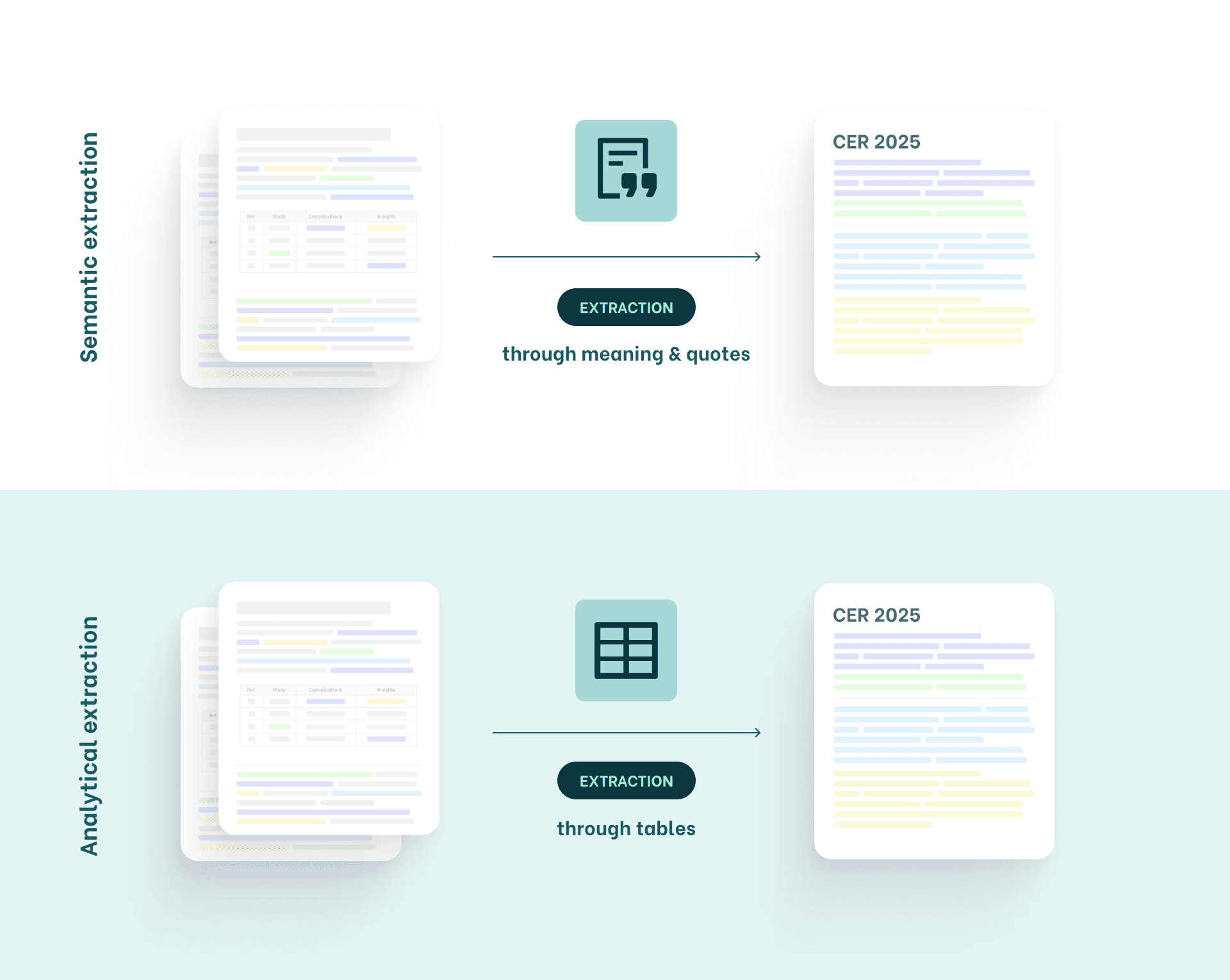

System A: Semantic Extraction

Extraction focusing on meaning, arguments & quotes

Semantic extraction is the system most clinical writers use.

Not because they planned it, but because it’s how humans naturally process information.

What semantic extraction looks like in the wild:

You open a PDF. You read.

You mentally extract arguments.

You copy a sentence into Word because “that sounds important.”

You highlight a paragraph in yellow because Future You will surely remember why. (Spoiler: You won’t.)

You shape arguments. You adjust your discussion.

You jump back to the paper. You add a quote. You remove it again.

It feels like this:

“This quote supports safety.”

“This paragraph shows long-term outcomes.”

“Study B contradicts Study A, I need to mention this.”

“Let me add this sentence to my conclusion.”

Semantic extraction resembles a debate:

“When you debate with five or six people, you don’t remember every number, you keep the meaning and form an opinion.”

It’s fluid. Nonlinear. And impossible to predict.

You never know …

how many papers you’ll end up using. This will depend on how ‘strong’ your argumentation feels to you.

what arguments will matter most,

what new questions will appear mid-writing,

or which snippet will become the backbone of your discussion.

In practice, semantic extraction has one fundamental limitation:

Meaning cannot be easily traced back.

Arguments blend together.

Sources fade into context.

Accessibility for others is difficult.

Statistics becomes complex.

And because meaning evolves while you write, completeness is impossible to guarantee.

And yet, this is how most of MedTech works today.

Can technology help here? Certainly!

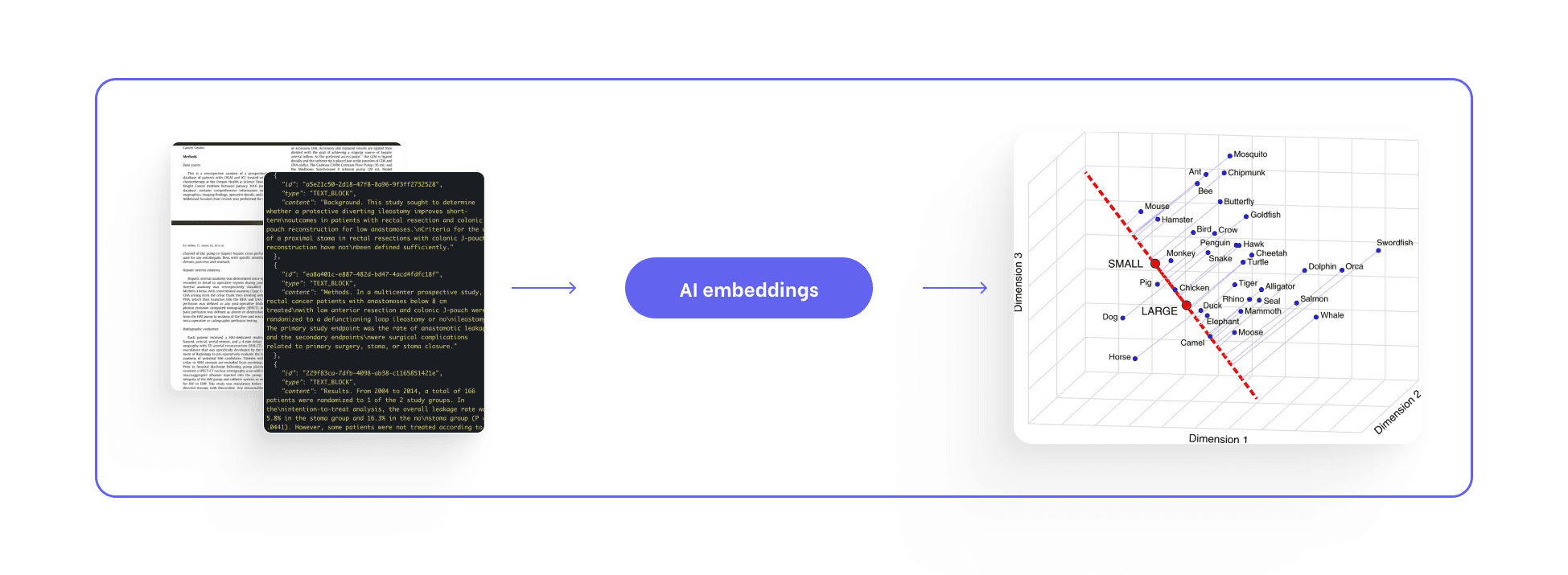

One important thing to keep in mind: a machine never sees a paper the way we do.

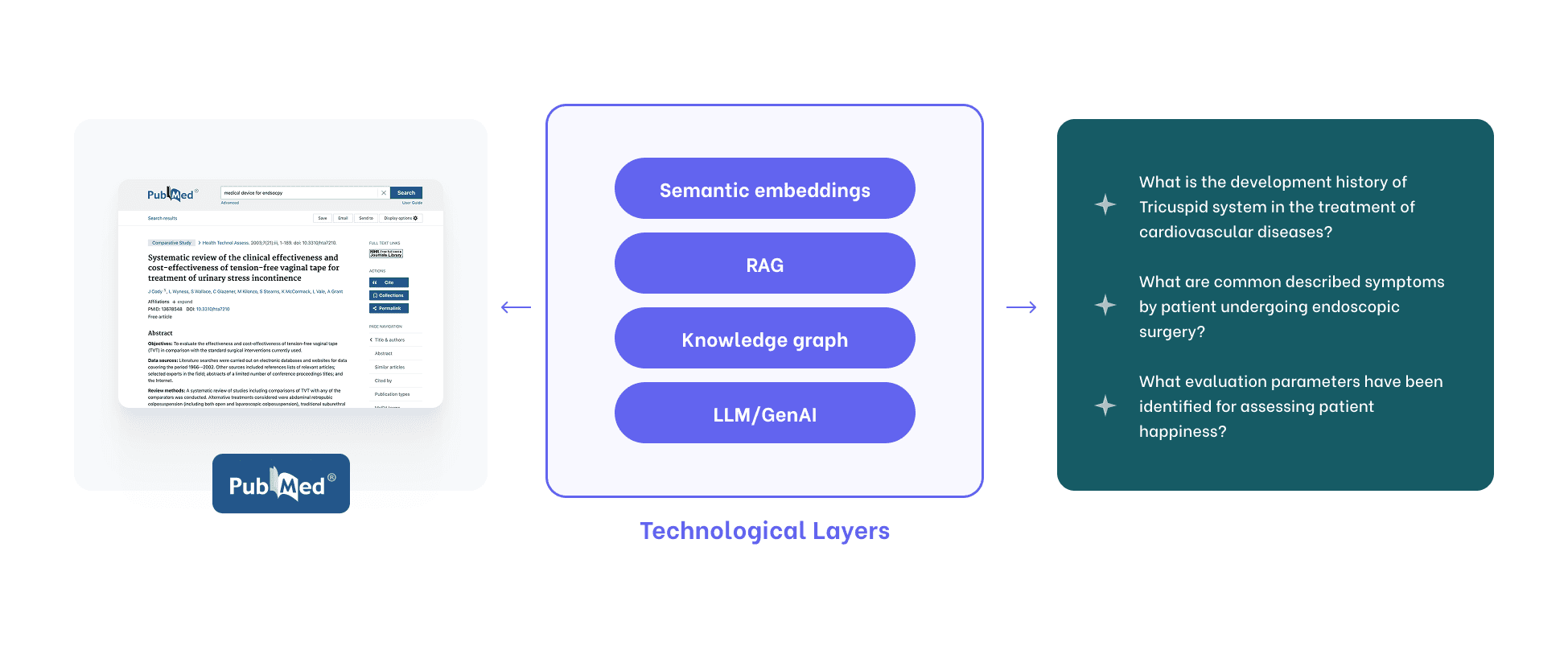

Semantic extraction requires multiple technology layers that together try to approximate how humans work with meaning.

Machines can retrieve, compress, and store the semantic content of an entire scientific paper. In theory, nothing is lost.

Arguments remain.

Context remains.

Relationships and nuance are all preserved.

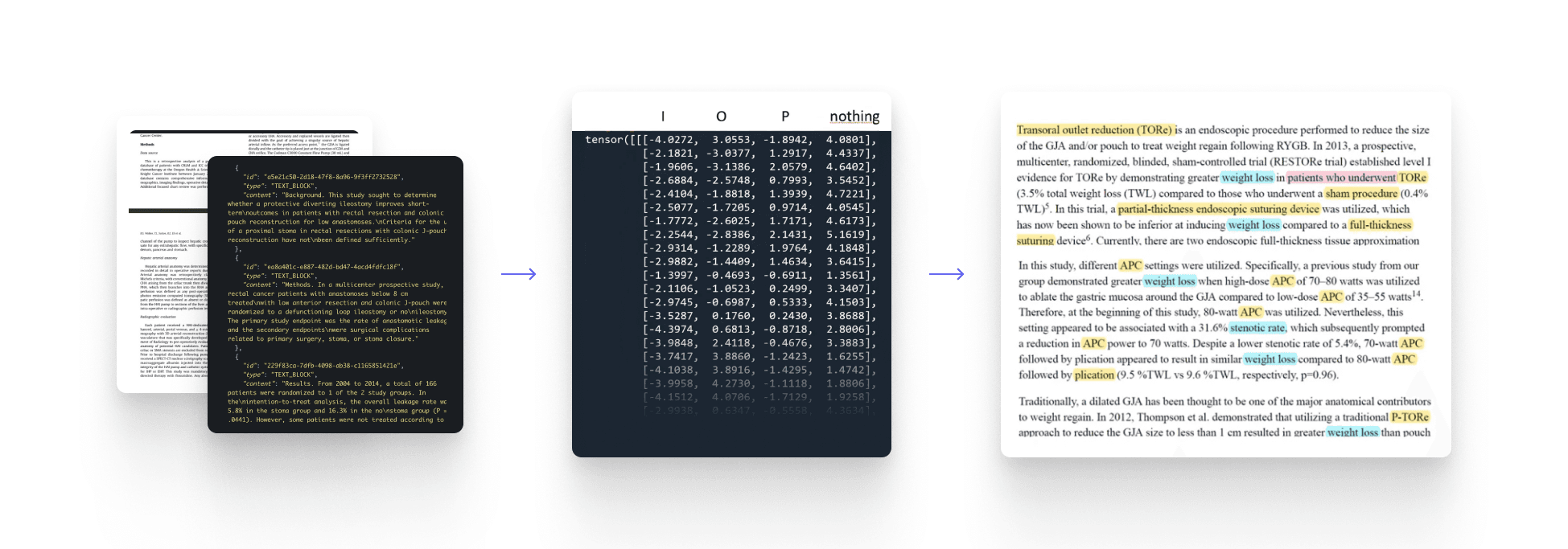

Unstructured literature is ingested from PDFs, PubMed, and internal reports.

Text is cleaned, normalized, and broken down into entities: diseases, devices, variants, outcomes.

Ontologies bring order.

Relationships are mapped.

Everything ends up in a growing semantic knowledge base.

Once processed, the information does not simply flow into a document and disappear.

It becomes structured, standardized, and persistently accessible.

Entities are aligned through medical ontologies.

Relationships and events are extracted.

Knowledge is stored in a way that can be revisited, queried, and reused over time.

In this sense, semantic extraction succeeds at what it promises:

meaning is preserved, comprehensively and at scale.

But this preservation is indiscriminate.

Alongside the 40–60 arguments that typically matter for a CER, the system retains everything else as well.

Peripheral observations.

Background explanations.

Context that is clinically correct, but not necessarily relevant.

Semantic extraction captures meaning faithfully,

including a large amount of clinical noise.

But should we even support medical writing in doing this?

Semantic extraction is very good at this:

preserving all meaning, detached from purpose.

With perfect embeddings, perfect ontologies, and flawless retrieval, the result is an ever-growing reservoir of preserved context.

Arguments accumulate.

Relationships remain.

Nothing disappears.

But structural limitations quickly become hard to ignore.

Precision is difficult to evaluate.

Accuracy is hard to define.

Traceability becomes fuzzy.

And because these systems are built around meaning rather than data, they do not naturally support statistics, calculations, or trend analysis.

Combined with the high computational and operational cost of building and maintaining semantic systems at scale, this led us, together with our customers, to explore a different extraction methodology: analytical extraction.

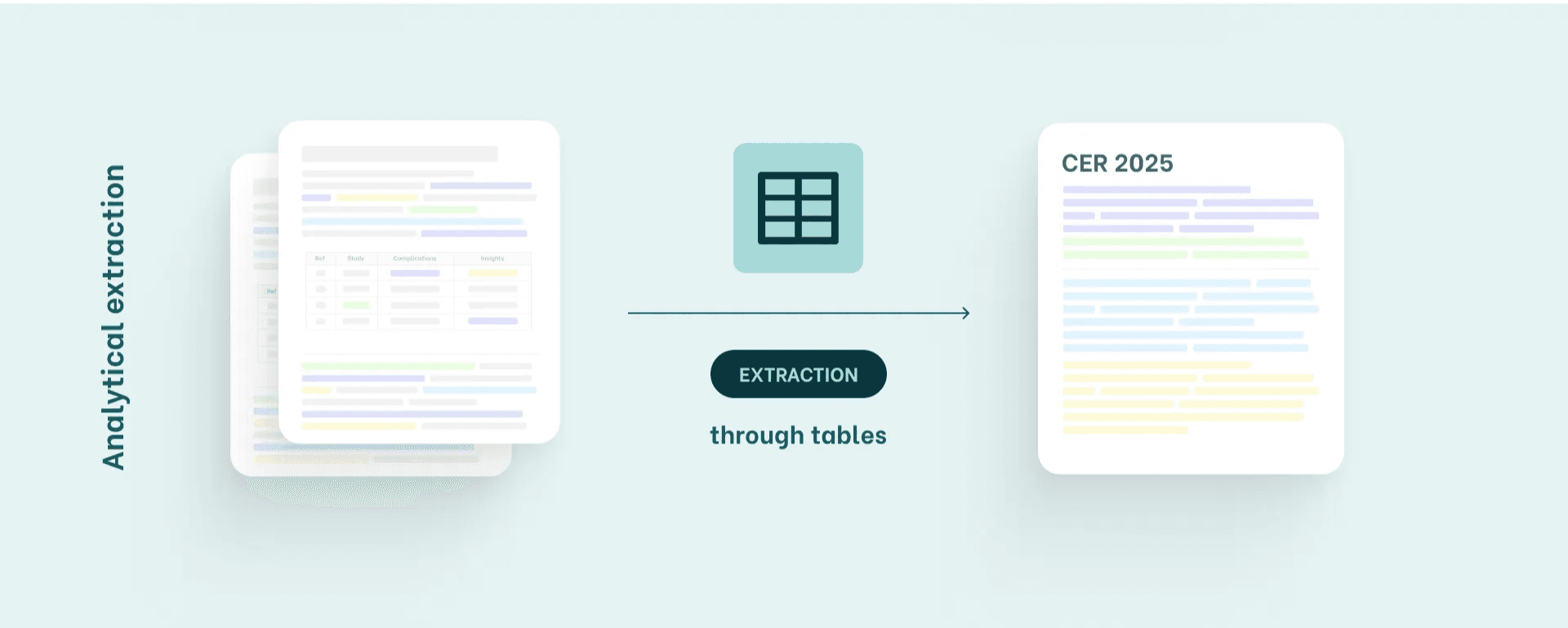

System B: Analytical Extraction

Extraction through structured data, tables & numbers

This method is common in teams working with complex devices (Class IIb/III) or stricter MDR/IVDR expectations.

What analytical extraction looks like

Before even reading, teams define exactly which data points they need:

number of patients, study type, complication rate, device characteristics, mean/median age, follow-up duration, and key outcomes.

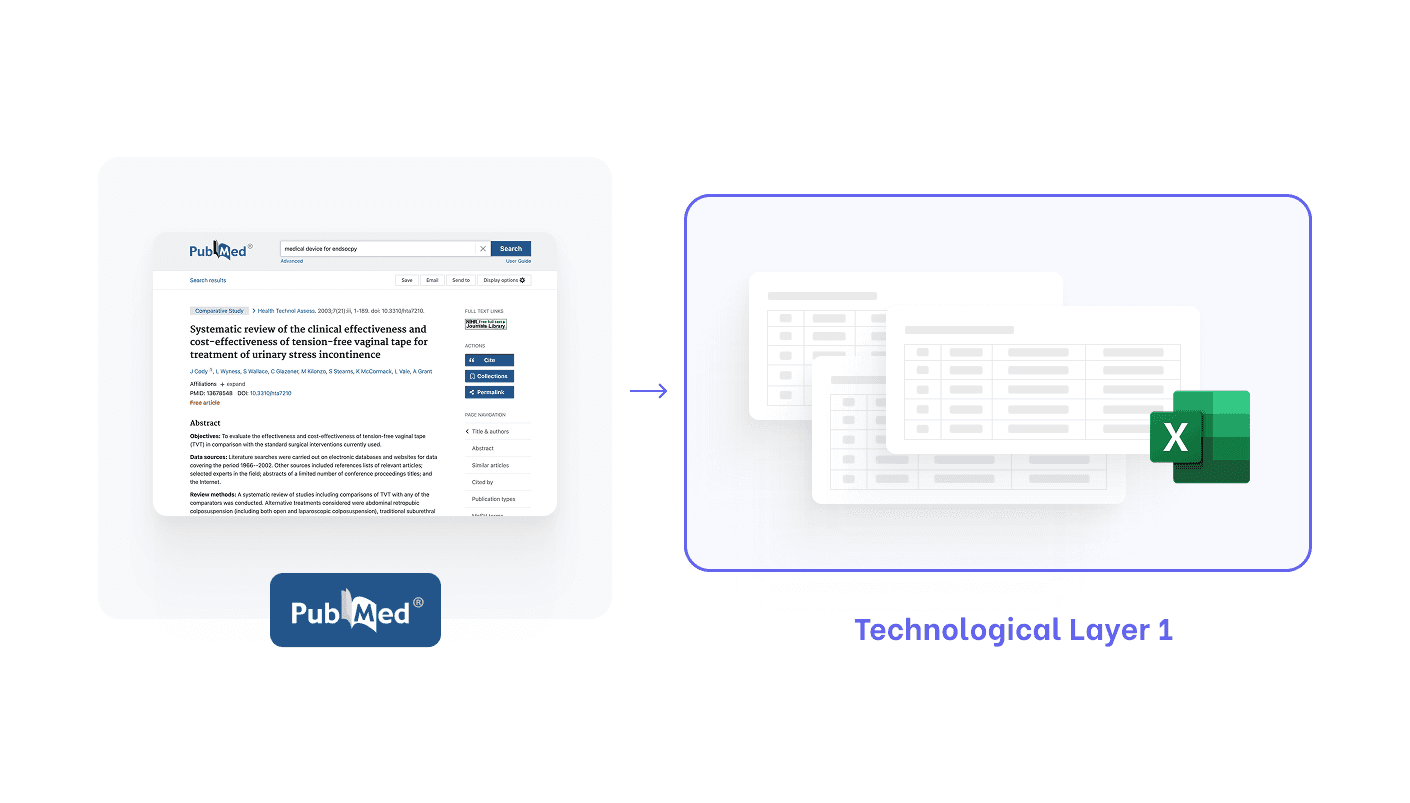

They build a structured table, often in Excel.

Then extraction becomes:

Extract numbers → Fill tables → Convert into paragraphs

(Orderly, auditable and predictable.)

What these teams need:

Perfect accuracy

Complete traceability to the sentence

Device-specific extractions

This system is not about meaning; it’s about evidence as data.

Supporting analytical extraction with AI is more straightforward but also more rigorous.

Can technology help here? It is meant to.

Supporting analytical extraction was never about a single technological bet.

It required working through several approaches and their limitations.

We started with general-purpose language models.

They were quick to test. Inexpensive to deploy.

But they produced too much unreliable output.

Too many false positives.

Too much clean-up.

Too little confidence.

From there, we moved toward more guided systems.

Expert definitions introduced clearer boundaries.

Precision improved.

Results became more consistent.

But reliability only emerged once all pieces came together.

Analytical extraction became scalable when expert-designed extraction fields, trained models, and built-in validation were combined into a tightly controlled system.

Only then did results become consistent, trustworthy, and ready to use.

This layered approach, not a single model, is what finally made analytical extraction reliable at scale.

Why Flinn Prioritises Analytical Extraction (And What That Means Going Forward)

Because of one simple principle:

It’s easier to go from numbers → meaning than from meaning → numbers.

Semantic extraction continues to play an important role.

Teams use it to explore early ideas, identify emerging complications or innovations, and ask high-level questions that require contextual answers.

But as literature reviews mature, analytical extraction tends to take the lead.

By integrating AI-supported analytical extraction into their workflows, teams move from interpretation to structure.

Validated numbers become reusable data.

Trends and statistics become easier to compute.

And clinical writing accelerates, because tables and well-formed paragraphs can be generated directly from trusted inputs.

Both extraction methodologies are real.

Both are valid.

But once AI enters the workflow, the underlying logic reinforces itself.

Starting with analytical extraction is therefore not about choosing a “winner.”

It’s about establishing a foundation teams can rely on.

Semantic extraction will continue to be useful, aside of systematic reviews, as a way to explore meaning and context at scale. And it becomes far more powerful once strong, structured foundations are already in place.

Final Thoughts: Where the Real Work Happens

Extraction rarely gets the spotlight, yet it’s the point where raw text becomes evidence and where AI can make the biggest real-world impact.

Our approach at Flinn is simple:

Begin with what delivers accuracy, traceability, and regulatory confidence. Then build upward into meaning.

And looking forward, the picture sharpens:

Analytical extraction will help MedTech teams become more data-centric and turn extraction into a reusable asset, not a one-off Excel task.

Semantic extraction will continue to evolve to support all non-systematic research.

And the future of MedTech literature work?

It will belong to the teams and technologies that bring both worlds together with intention, not to follow trends.

Curious how data extraction works in your own workflows? Contact us.